Lessons for my Lifetime

When I was six years old I told my coach, Mr. Moynihan, I couldn’t make our game because I was attending a Green Bay Packers game. “You don’t miss your game for someone else’s game Robbie!” he screamed at me with disgust and loathing. At least that’s how it felt to me then.

I went home, cried and said I didn’t want to go back to soccer. The next afternoon my mom and I visited Mr. Moynihan at his business, Demand and Precision Tool Parts. He looked even scarier, all 6’2” of him in coveralls, his face and hands smudged with grease.

“Get yourself a soda out of the machine over there”, he told me. I went to the soda machine but didn’t have 50 cents. “Just open the door and pull a soda out.” I touched the door hesitantly. “Go ahead open it,” he urged. I pulled it open and voila, I felt like Charlie Bucket[1] with about 500 bottles of soda to choose from! I grabbed something purple. Then Mr. Moynihan smiled and said, “It’s okay if you go to the Packers game.”

Looking back, I don’t think he meant it. He must have been saying it for my mother’s sake. The Mr. Mo I know would never be okay with someone skipping his own game to watch another game. But I was young and naïve, swayed easily by a free soda and pleasant visit. Behind the big booming voice and grease-smudged demanding persona, he was nice. I started liking him.

One time when I was about eight years old, I was playing soccer with the Moynihan boys (John and Mike) in their backyard. Everyone gravitated to their yard. Four Moynihan kids with parents who genuinely liked kids and enjoyed having them around made for a great setting. At suppertime, they asked me if I wanted to stick around for dinner. Never one to pass up food, I jumped on it, though with a couple of caveats. I was told mashed potatoes were on the menu. “I love mashed potatoes,” I said. “But they’re not boxed, are they? I don’t eat boxed mashed potatoes.” Let me explain: my mom always made a big deal out of never serving boxed mashed potatoes. It was a true source of pride for her. “You know I never make boxed mashed potatoes. I make them from scratch,” she’d proclaim, her arm twisted in an awkward angle to pat herself on the back. I just assumed this was a Harrington trait, “No offense people, but unlike you bourgeois plebes we Harringtons do not partake of boxed mashed potatoes.”

Mr. Mo responded, “You’ll eat whatever mashed potatoes we put on your plate.”

“Not boxed ones,” I replied nonchalantly. Obviously, he didn’t understood our family rules.

The Moynihan kids stared at me wide-eyed – one of those are you crazy looks.

“Well I guess you’re not eating dinner then!” Mr. Mo grabbed my plate off the table. Seconds later Mrs. Mo, wearing a wide smile, brought my plate back. She was giggling. “Robbie, you have nothing to worry about; these are real potatoes.”

The Big Guy (one of Mr. Mo’s nicknames) had definitive rules on proper etiquette. He was always teaching more than soccer. Being a gracious guest mattered, attending your team’s games mattered, pageantry did not. When our team qualified for the Midwest Regional Championships, he wanted to boycott the opening ceremonies – the all-teams parade. All that flouting of feathers and pomp and circumstance irritated him to no end. As a result, we didn’t wear our uniforms and a few times over the years we barely fielded a team for the ceremony.

“Parade’s,” the Big Guy said, “phony bullshit!”

On the other hand, when we drove to tournaments, he enforced strict travel etiquette rules. “Everyone, off with the headphones,” he’d command. “We’re going to have conversations. We’re going to talk to each other like human beings.”

“Let’s talk about sex,” I suggested. That time he let us go back to our headphones.

At a time when all the best soccer coaches were first or second-generation immigrants Mr. Moynihan was a born, bred, multigenerational American. Despite this drawback, we won anyway. The secret to his success was not complicated: Mr. Mo loved kids and he loved being around them. He loved their enthusiasm and energy and was never shy about giving advice. As a coach, he was a logician. To this day, I try to emulate his thoughtful lessons on soccer and life. His approach stuck with me: the ceremony doesn’t matter, showing up for the game ready to play does.

Mr. Mo was a great youth soccer coach not because he had an extensive soccer background. He was great because he never stopped learning. And he also was humble enough to know when it was time to turn us over to a new coach. After five consecutive trips to the Midwest Regional Championships that’s exactly what he did, deciding these kids are older now, I’ve had them for a long time – it’s time for someone new.

My Senior year in high school Mr. Mo offered me a job at Keeper Goals, aka Demand and Precision Tool Parts, the place with the free soda. After years of playing for Mr. Mo this was perfect. The Big Guy would continue to mentor me; but now instead of kicking a ball I’d be learning how to grind, cut and clean steel.

“I can sweep the floor faster with my tongue,” is the first mentoring line I remember coming from him as I attempted to revolutionize centuries of sweeping technique by demonstrating the advantages of the pull technique over the more traditional push technique. He grabbed the broom from my hand and began pushing the broom at a pace no mortal could ever maintain and said rather snidely, “This is how you sweep Harry, you push. Got that?!”

I gathered from his facial expression that he wasn’t looking for an answer to his question. I vowed to do better.

One day, I was cleaning crossbars with some toxic solution. I don’t recollect the exact number of crossbars, but it was higher than I can count; each took about 15 minutes to clean. After hour two I developed acute lower back pain from bending and my work rate slowed. Despite the pain, I labored on. When Mr. Mo approached, I expected high praise for my diligence. “Look at that shine,” he’d likely say. “Really nice work. I know this is hard on the lower back Harry and I appreciate your fortitude. You always were one tough son of a bitch.”

“Thanks,” I’d wince, touching the small of my back, then continue my work while he contemplated the amount of the raise he was going to give me.

Nope.

“Harry it’s not a damn art project, just clean the damn things,” he yelled. “You only have six done? What’s taking you so long?”

“My back really hurts.” (It wasn’t exactly a whine.)

“Then put something else under the crossbars so you don’t have to bend down so far.”

Duh!

One day I stopped him at work. “Big Guy I have some good news for you and some bad news. What do you want first?”

“I guess I’ll take the good news Harry.”

“I’m quitting.”

“Okay,” he deadpanned. “What’s the bad news?”

“Not for another two weeks.” I might not have been his employee of the year but that comment did get a chuckle out of him.

The Moynihan kitchen was our gathering place. Mr. and Mrs. Mo spent hours in their kitchen listening intently to current and former players tell stories, complain and ask for advice. One year, I sat at the table offering up tale after tale, laced with some humor and a healthy dose of complaints and self-pity, about my latest soccer playing season. The Big Guy laughed, smiled, and nodded, then said, “You know what Harry. You’re a big baby! Why don’t you just shut your mouth and play soccer.”

At that moment, my life, at least as it relates to all thing’s soccer, changed. Over the years, Mr. Mo offered me numerous soccer and life lessons, but that single comment hit me like a lightning bolt. It’s the single most meaningful and influential comment in my soccer life. Today, it’s a mainstay in my soccer lexicon; it’s the cornerstone of my coaching philosophy. I envision it as a “Successory” poster. Here’s the image: a disheveled and distraught player, hands gesticulating and mouth agape, stares up at a coach figure. The lighting and mood are dark with just a hint of sunlight illuminating a game going on behind them. Above the photo the caption reads, “You’re a big baby! Why don’t you just shut your mouth and play soccer.” Seriously Successories, if you are reading this, make the poster, it’s a guaranteed top seller. At least, I’ll buy it.

In 1992, at the age of 47, Mrs. Mo died of cancer. It was a devastating loss for the entire family. Mr. Mo struggled. He took up cooking as a hobby. I wanted to be present for my coach and his kids, my friends, so I showed up nearly every day at suppertime for around seven years. Mr. Mo and I got closer. I’m not saying emotionally wrought conversation followed by a cathartic epiphany closer. I’m talking wild opinions flying, stories rehashed, insults tossed, memories questioned, and endless plans developed closer. We had fun and though no formal declarations were made, I’m pretty sure he enjoyed watching my coaching career unfold.

In 1995 my girls high school team was in the state finals. I was recovering from ACL surgery and decided I wanted to bicycle the 40-some miles to the game in order to get in some PT. “Good idea, Harry,” Mr. Mo said. “I’ll go to your game and drive you home afterward.”

After the game we stopped at a bar for a beer and I told him I wanted to bike around New Zealand. “Let’s do it,” he responded.

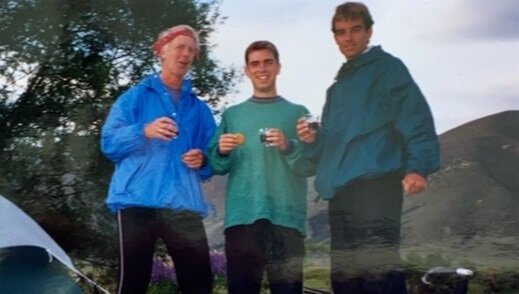

And so we did. On the fourth day of our trek across New Zealand, Mike (Mr. Mo’s son), Mr. Mo (52 at the time) and I had ridden our bicycles about 50 miles before we stopped at a small restaurant/bar by the side of the road. Mr. Mo didn’t say it, but he looked tired. “How much further is it to Geraldine?” he kept asking us. Some sheep shearers at the table next to us said about 35 kilometers.

Mr. Mo slouched, then laughed. He bought the sheep shearers a round of beers and started asking them about their trade: what’s the technique, how many can you shear in a day, who uses the wool, are the sheep also used for meat? Lessons taught by Mr. Mo aren’t always spoken, they’re witnessed. Creating good will through curiosity about others – a lesson well worth learning.

After an hour or so, Mike asked our new friends if they would drive Mr. Mo to Geraldine. We packed his bike and bags in the back of their pick-up, and waved him off cozied between two Kiwis in the front seat.

Mike and I took our time getting to Geraldine, stopping to fish and hike along the way. We arrived at dusk and found the campsite but not Mr. Mo, his bike or his tent. We were a bit worried. Maybe they took him to the wrong town. Was he robbed? Abducted? Was he that very moment being held hostage? Would he become slave labor cutting steel and making sporting equipment for those treacherous Kiwis whom we thought were our friends?

Mike, genius that he is, had a thought. “Let’s check that hotel over there.” I waited outside with our bikes and bags picturing a bruised and beaten Mr. Mo limping down the road after being robbed of all his belongings. Mike finally came back.

“Go into the bar. I’ll wait with our stuff,” he said.

“Why?”

“Because you’ll want to see this.”

Mr. Mo, there he was, freshly showered and wearing a salmon-colored button-down shirt swilling beer with a table of sheep shearers.

The man knows how to make friends.

For a very short while in 1998 I parked my car at Mr. Mo’s house. It was a generous offer; without that parking spot I would have had to move out of my residence. He had one condition – I had to mow the lawn. He didn’t give me a mowing schedule figuring, I guess, that I was smart enough to tell when grass was getting long. I arrived on a Saturday to mow the lawn for the first time, but Mr. Mo was out there mowing. When I approached, he barely acknowledged my presence. Eventually, he stopped mowing but didn’t turn off the mower.

“I came here to mow the lawn,” I yelled over the engine noise.

“Too late Harry,” he responded, preparing to drive away.

“What?”

“Too late. You need to find somewhere else to park.”

“Really? You never told me when to mow the lawn.”

“Too late Harry. Parking privileges revoked,” and he returned to mowing.

I left his house annoyed but not really surprised. Our relationship, though it had changed some, ultimately wasn’t much different from when I was a kid – Mr. Mo was teaching me a lesson.

I headed home. I saw my next-door neighbors, whose kid I coached, and told them I needed to move because I didn’t have a parking spot. On the spot, they offered me free parking. I offered to mow their lawn or do something in return, but they wouldn’t hear of it. They did set aside a day to feed me ice cream cake and try to convert me to their form of Christianity. Hey, the parking spot was well worth every bite of the delicious cake and free theological advice.

The next night I returned to Mr. Mo’s for dinner. We talked, joked and he finally asked me, “So where are you parking?”

“My neighbors,” thanks for asking. “They gave me a spot for free, so everything worked out.” I flashed him a big broad smile. He looked slightly confused. “It really worked out great,” I added, really laying it on thick. “It’s right next door so I don’t have to walk two blocks like I did when I parked here.” Mr. Mo pursed his lips and nodded. “So, actually you kicking me out really helped. From the bottom of my heart – thank you.” I continued to smile broadly until we both started giggling.

Mr. Mo is in his 70s now. He lives in Beechwood, Wisconsin on a farm with his girlfriend Judy. His daily tasks include caring for his chickens and goats, moving dirt around, watering, gardening and building or planning new additions to the farm. I visit on occasion, stay overnight. He or Judy cook and the meal is always delicious. Then we tell old and new stories. Though Mr. Mo’s a friend now, he’ll never stop being my mentor and coach. But he has eased back on the advice—probably because, these days, I have my own parking space.

[1] Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory Charlie Bucket.